Diagnosing asthma in children aged 5-16

The information in this section will help you to understand the fundamentals of diagnosing asthma in children aged 5-16 in the primary care setting. For children aged under 5, please see this page.

This is not a substitute for completing an appropriate respiratory assessment module. For advice and support on choosing the right course for you, please see our training and development page.

About the guidelines

A joint asthma guideline was produced in November 2024 by NICE, BTS and SIGN. This guideline recommends a new approach to diagnosing asthma in a both adults and children.

The guideline re-examined the evidence and concluded that with a detailed clinical history that suggests someone might have asthma then a single test can be used to confirm asthma.

Diagnosis is made by:

- taking a thorough history from the child and their parent/carers, and then

- undertaking a sequence of objective tests.

If you still think someone has asthma but the tests are negative then referring for expert opinion and further testing is needed.

You can also refer to the NICE Clinical Knowledge Summary for more information, and PCRS’s First Steps guide.

Asthma in children and young people

- Asthma is the most common long-term medical condition in children and young people in the UK, affecting around one in 11 - that’s 2 -3 children in every classroom.

- Poorly controlled asthma limits children’s ability to sleep, grow, play and learn.

- The UK has one of the highest asthma mortality rates among children and young people in Europe.

- Children are less likely than adults to receive good basic asthma care. Fewer than 25% of children with asthma have a personalised asthma action plan (PAAP)

- Poverty makes children’s outcomes worse. Children in the most deprived areas of England have higher admission rates and are four times more likely to die from asthma compared to those in the least deprived areas.

- Studies show that 2.8 million school days are lost every year because of asthma symptoms.

Taking a structured clinical history

Early and accurate diagnosis is key to enabling a child to live well with their asthma.

This is made by:

- taking a thorough history from the child and their parent/carers, and then

- undertaking objective tests.

Use the guide below to help you to ask the right questions. You can send our How to Spot Asthma in your Child video to parents and carers before their appointment, so they can start thinking about their child’s symptoms. It’s really helpful if they can record their child’s symptoms on their phone, too.

| Questions to ask the child/their parent | Why these questions matter |

|---|---|

|

Do you get a cough that comes and goes? Does the cough happen even when you are well and able to play as normal? Do you cough when running around? Does anything make the cough worse, like the weather, smoke, perfume, dam or mould or car fumes? |

Asthma is a variable condition, and cough is a common symptom. A cough that is continuous is less likely to be asthma . Don’t forget to think about differential diagnosis of cough in children. A cough that happens when the child does not have a viral infection and is in response to a trigger is more likely to be asthma. Symptoms in response to triggers make an asthma diagnosis more likely. This question can help to identify triggers if having episodes mainly when at/near home. Common triggers include exercise, cold weather, dust and mould, smoke exposure, pollution, allergens, emotion and viral infections. |

|

Do you get a tight feeling in your chest that makes it hard to breathe? Do you get tummy aches? |

Chest tightness is a symptom of asthma and is often caused by untreated inflammation in the airways. Children are more likely to describe chest tightness as a tummy ache. This is because their perception of internal body sensations (interoception) is still developing. Chest discomfort from the diaphragm can feel like tummy ache because the nerves supplying the diaphragm and abdomen are connected. |

| Is your chest or your breathing ever noisy? What does it sound like? | Avoid using the term 'wheeze' as this will be different for each person. Instead, ask them to describe how their child’s chest sounds or record them on their phone if they can. |

| Are episodes diurnal (i.e. worse at night or in the morning)? | Night-time or early morning symptoms are a sign of uncontrolled asthma. |

| Do you have hay fever, eczema, allergies? Ask about food allergies too. | Allergic disease and atopic (allergic) dermatitis increases the likelihood of asthma. |

| Is there a family history of asthma or allergy? | Asthma in immediate family members, especially maternal asthma, makes asthma more likely |

| Were you born prematurely? | Premature birth, defined as delivery before 37 weeks of gestation, has been associated with an increased risk of developing asthma in both childhood and adulthood |

Physical examination

Assess if the child looks well, check their weight and height and look for any signs of faltering growth. Accurate weight and height will be useful in future for calculating predicted peak flow and it is important to monitor growth for children on inhaled cortico-steroids.

Check for finger clubbing, wet cough, vomiting and any other signs of alternative diagnosis. Refer the child to their GP if you have any concerns.

If you are trained to, listen to the child’s chest. If they are symptomatic when you listen, you may hear an expiratory polyphonic (multiple pitches and tones on the out breath) wheeze over different areas of the lung. Remember, not all children with asthma wheeze. Absence of wheeze does not rule out asthma as a diagnosis.

Watch this video to hear lung sounds associated with asthma.

Safety note: this video is for information only and does not constitute training.

Review the child’s notes

Most NHS IT systems allow you to make searches of your patient’s notes. This is quick and easy to do and can help you find information you can use to decide if someone is more or less likely to have asthma. Look for:

• GP practice or out of hours/ ED attendance with an acute chest symptoms.

• Previous chest symptoms, including any chest infections.

• A record of an HCP hearing a wheeze.

Look in the medications list. Has the child ever been prescribed any:

• Inhalers

• Oral steroids

• Antibiotics for chest symptoms?

Have they ever had a raised blood eosinophil count? Having a blood eosinophil count >0.5 ×10⁹/L is a marker for asthma. However, there are other causes of raised eosinophils in the blood, such as allergy, infection and connective tissue or inflammatory disorders.

Childhood symptoms may not have been recorded as asthma, but they may have been labelled as 'wheezy bronchitis’ described as a 'chesty child' and these could suggest previous undiagnosed asthma symptoms.

If you think the clinical history and examination makes you suspect the child has asthma add the read code "suspected asthma", document all your findings so far and start diagnostic testing.

Diagnostic testing

Although the updated NICE guideline recommends that 1 objective test is required to confirm asthma, QoF currently requires HCPS to perform 2 objective tests to do so. This is because QOF 24/25 is based on the earlier version of the NICE guidelines.

This is currently being updated for the 25/26 QOF year. Until these are updated in April 2025 to satisfy QOF you still need to have 2 tests to confirm asthma.

Tests should be carried out in the following order, when available:

FeNO

Test 1: Measure FeNO (Fractional Exhaled Nitric Oxide)

FeNO testing measures nitric oxide, an inflammatory biomarker which is produced in the airways and detected in exhaled breath .

Eosinophilic inflammation is the most common type of inflammation seen in asthma and it usually responds very well to inhaled corticosteroids.

The FeNO level will go up if there is untreated eosinophilic inflammation in the airways and this can help you to decide whether someone has asthma or not. There is a free training on FeNO testing available here.

FeNO can also be used to help patients understand and visualise the airway inflammation linked to asthma diagnosis, and also as a measure of how effective their medication is. It can be a great tool for adherence and motivation, too. NICE recommends using FeNO when monitoring asthma and especially if changing medication

FeNO results can be affected by several factors. High FeNO can be due to allergic rhinitis or nitrate rich foods such as green leafy vegetables (for example, celery, leek, beetroot, lettuce and spinach).

Exercise may also raise FeNO levels, whereas caffeine, alcohol, and tobacco may decrease FeNO levels.

An information video for children can be sent to your patient, and PCRS have a multi lingual range of leaflets advising parents of foods and activities to avoid ahead of their appointment.

Take a look at this FeNO Toolkit, which includes information for you and your patients including templates, AccuRX messaging as well as help developing business cases for getting FeNO.

Interpreting FeNO results

A FeNO level >35 ppb is a positive test, and you can make your diagnosis based on this result. No further tests are required at this stage. Document the result and add the read code "asthma".

If the FeNO test is negative or not available, proceed to the next step.

Spirometry testing

Test 2: perform bronchodilator reversibility (BDR) spirometry testing.

Spirometry is an objective diagnostic test which must be quality assured. It should only be performed and technically reported by an HCP who has undergone appropriate training.

The ARTP Spirometry National Register is a list of HCPs who have completed the ARTP Spirometry Certification. Joining the National Register is not mandatory, but it ensures that all HCPs have their skills assessed and are certified as competent. You should have completed training that is appropriate for children before carrying out spirometry on them. For advice and support on choosing the right training for you, please see our training and development page.

Spirometry with reversibility is the objective test for asthma. Many children aged 5 can perform spirometry. You can send children this video ahead of their test.

You can diagnose asthma if the FEV1 increase is 12% or more from the pre-bronchodilator measurement (or if the FEV1 increase is 10% or more of the predicted normal FEV1)

Remember: if the child is not symptomatic on the day when they are tested, their spirometry may be normal. This doesn't mean they don't have asthma!

If BDR testing is positive, asthma is likely. Document the result and add the read code "asthma".

If BDR Test is inconclusive, or if spirometry is unavailable move to the next step.

Key guidance for performing and interpreting spirometry

Peak flow monitoring

Test 3: peak flow monitoring

Peak flow monitoring is an option if you do not have access to spirometry, or there are long waits for it.

PEF in patients with asthma is usually lower in the morning and higher in the evening. This is called diurnal variation.

For accurate results the PEF should be recorded at least twice a day, on waking and ideally around 4pm when peak flow tends to ‘peak’. The child should perform at least 3 blows and record the highest number. The diary should be kept for 2 weeks. Here’s a video to send to your patient.

If diurnal variation is 20% (expressed as amplitude percentage mean) you can diagnose asthma. Document the result and add the read code "asthma".

Use our calculator to work out your patient’s percentage

If asthma is not confirmed by FeNO, BDR or PEF variability but still you still think that asthma is likely given the clinical history, proceed to:

Allergy testing

Test 4: testing for allergy markers

Perform skin prick testing for house dust mite (HDM). A positive skin prick test to HDM in someone with a good history of asthma will confirm asthma diagnosis. Here is a video for children about having skin prick testing.

or

Measure serum IgE and blood eosinophils. A positive result is a raised IgE AND Blood eosinophils >0.5 ×10⁹/L.

Document the result and add the read code "asthma".

If allergy testing is negative and the child is still symptomatic, refer back to the child’s GP as the child may either have an alternative diagnosis or need referral to a respiratory paediatrician for further assessment and possibly a bronchial challenge test.

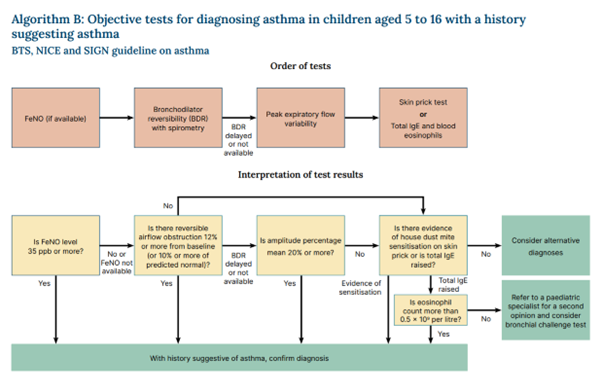

These steps are shown in the diagram below.

If the child you are assessing is acutely unwell, you should not delay treatment whilst you wait for testing. A symptomatic child presents the ideal opportunity to perform spirometry with reversibility, or peak flow reversibility testing.

To perform peak flow reversibility:

• Record a pre bronchodilator PEF (best of 3 blows)

• Give a dose of salbutamol (400 μg via an inhaler and spacer device).

• After 15 minutes, record a post bronchodilator PEF (best of 3 blows)

Variation of 20% is suggestive of asthma.

To calculate:

You can also perform FeNO testing when the child is symptomatic, but be aware that FeNO may falsely raised if the child has allergic rhinosinusitis or viral illness.

Having made your diagnosis and documented it, you can now move onto treating the child's asthma.