The information in this section will help you to understand the differences between preschool wheeze and suspected asthma in children aged under 5, and how to manage their care.

This is not a substitute for completing appropriate education and training such as a paediatric respiratory assessment module or accredited asthma course. For advice and support on choosing the right course for you, please see our training and development page.

For children aged 5-11 years of age, please see our information on managing asthma in children aged 5-11.

Key resources:

A joint asthma guideline was produced in November 2024 by NICE, BTS and SIGN.

You can also refer to the NICE Clinical Knowledge Summary for more information, and PCRS’s First Steps guide.

Wheezing in the child under 5 years old

- Wheezing in the under 5 age group is often referred to as ‘pre-school wheeze’ and is not the same as asthma.

- Preschool wheeze is common and affects approximately 30–40% of children under six years old.

- In most cases, preschool wheezing resolves as children grow older—about 60% outgrow it by the age of 6, and 80% by the age of 10.

- Only one in three children with preschool wheeze progress to an asthma diagnosis by their 6th birthday.

- It’s important to assess children carefully to avoid misdiagnosis of asthma and under or over treating them.

Preschool wheeze: causes and contributing factors

Viral Infections

Respiratory viruses like rhinovirus, respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), and adenovirus are the leading cause of wheeze in preschool children.

These viruses can trigger viral-induced wheeze, especially in children under three.

Airway size

Young children have small airways that are more prone to narrowing when inflamed or congested.

As the airways grow, many children outgrow their wheeze.

Atopy and allergic sensitisation

Children with a family history of allergies, eczema, or asthma are more likely to develop wheeze.

Sensitisation to indoor and outdoor allergens (such as house dust mites, pollen, pollution, mould, pets) can contribute to airway inflammation and wheeze.

Smoking

Exposure to tobacco smoke, both during pregnancy and after birth, increases the risk of wheezing.

Prematurity and low birth weight

Babies born prematurely or with low birth weight may have underdeveloped lungs, making them more prone to wheezing.

Gastro-oesophageal reflux

Reflux can lead to airway irritation, causing wheeze in some children.

Other conditions

Rarely, other conditions such as airway malformations, bronchiectasis, or bronchiolitis obliterans can cause wheeze.

Inhaled foreign bodies can occasionally mimic wheeze.

When to suspect asthma

Differentiating preschool wheeze from suspected asthma in children under 5 is often challenging. Making a diagnosis of asthma is hard in this age group because it is difficult to for them to do the tests and there are no good reference standards .

Therefore, children aged under 5 will usually be coded as ‘suspected asthma’ until they are old enough to perform diagnostic testing, which is generally around 6 years of age.

Assessing the child with suspected asthma

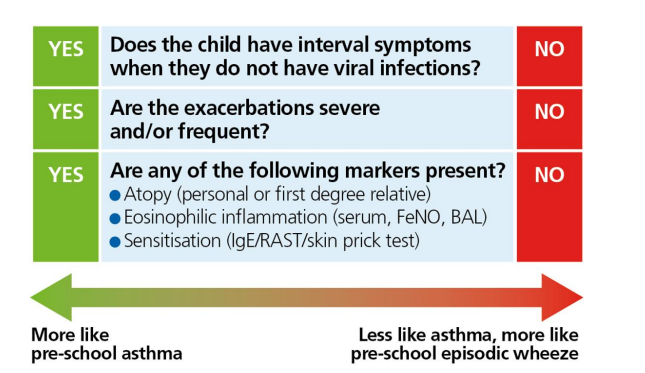

You firstly need to find out if it is more likely that the child has preschool wheeze or suspected asthma.

Use the guide below to help you to ask the right questions. You can send our How to Spot Asthma in your Child video to parents and carers before their appointment, so they can start thinking about their child’s symptoms. It’s helpful if they can record their child’s symptoms on their phone, too.

| Question to ask | Why this question matters |

| Is your child’s chest or breathing ever noisy? What does it sound like? | Avoid using the term 'wheeze' as this will be different for each person. Instead, ask them to describe how their child’s chest sounds or record them on their phone if they can. |

| When does your child have a noisy chest? Does it only happen when they have a cold? Does this happen even when your child is well and able to play as normal? |

Wheeze only during colds is often viral wheeze, which is usually transient. Asthma is more likely if wheeze occurs between colds or without infection , this is called an ‘interval symptom’. Exercise-induced wheeze is a classic asthma feature, reflecting airway hyperresponsiveness. Viral wheeze is less likely to occur with exercise. |

| Does your child have symptoms like a noisy chest, cough, or breathlessness at night or in the early morning? | Asthma symptoms often worsen at night due to airway inflammation. Night-time or early morning symptoms are a strong indicator of asthma . |

| Does your child have eczema, hay fever, or other allergies? | Atopy (eczema, hay fever, or allergies) is strongly linked to asthma development. Preschool wheeze with atopy increases the risk of asthma. |

| Is there a family history of asthma, eczema, or allergies (including food allergies)? | Family history of atopy (asthma, eczema, or allergic rhinitis) increases the likelihood that the child’s wheeze is asthma-related. |

| Have you noticed any specific triggers for your child’s chest symptoms (e.g., pollen, pets, dust, smoke, exercise, cold air)? | Symptoms in response to triggers make an asthma diagnosis more likely. Viral wheeze is less likely to have specific non-viral triggers. |

| Was your child born prematurely? | Premature birth, defined as delivery before 37 weeks of gestation, has been associated with an increased risk of developing asthma in both childhood and adulthood. |

The visual aid below will also help you to decide if preschool wheeze or suspected asthma is the most likely diagnosis.

Physical examination

Assess if the child looks well, check their weight and height, plot their centile and look for any signs of faltering growth. Accurate weight and height will be useful in future for calculating predicted peak flow and it is important to monitor growth for children on inhaled cortico-steroids .

Check for finger clubbing, wet cough, vomiting and any other signs of alternative diagnosis. Refer the child to their GP if you have any concerns.

If you are trained to, listen to the child’s chest. If they are symptomatic when you listen, you may hear an expiratory polyphonic (multiple pitches and tones on the out breath) wheeze over different areas of the lung.

Watch this video to hear lung sounds associated with asthma.

Safety note: this video is for information only and does not constitute training

Review the child’s notes

Most NHS IT systems allow you to make searches of your patient’s notes. This is quick and easy to do and can help you find information you can use to decide if someone is more or less likely to have asthma. Look for:

• GP practice or out of hours/ ED attendance with an acute chest symptom.

• Previous chest symptoms, including any chest infections.

• A record of an HCP hearing a wheeze.

Look in the medications list. Has the child ever been prescribed any

• Inhalers

• Oral steroids (prednisolone)

• Antibiotics for chest symptoms

• Treatment for allergies or eczema?

Document your assessment of the child and if you think that asthma is more likely than preschool wheeze, code the child as ‘suspected asthma’. You can then consider starting treatment.

The purpose of a trial of treatment is to see if it helps with the symptoms, and if they come back after the trial is stopped. A positive response (improved symptoms) suggests the child may have asthma and would likely benefit from ongoing preventer treatment.

If there’s no clear improvement, it may suggest an alternative cause, or the symptoms may be virus-related and not due to underlying asthma. Stopping the trial and assessing the child’s response ensures that the child is not over treated.

This does not comnfirm a diagnosis of asthma. This can only be done using objective tests when the child is older.

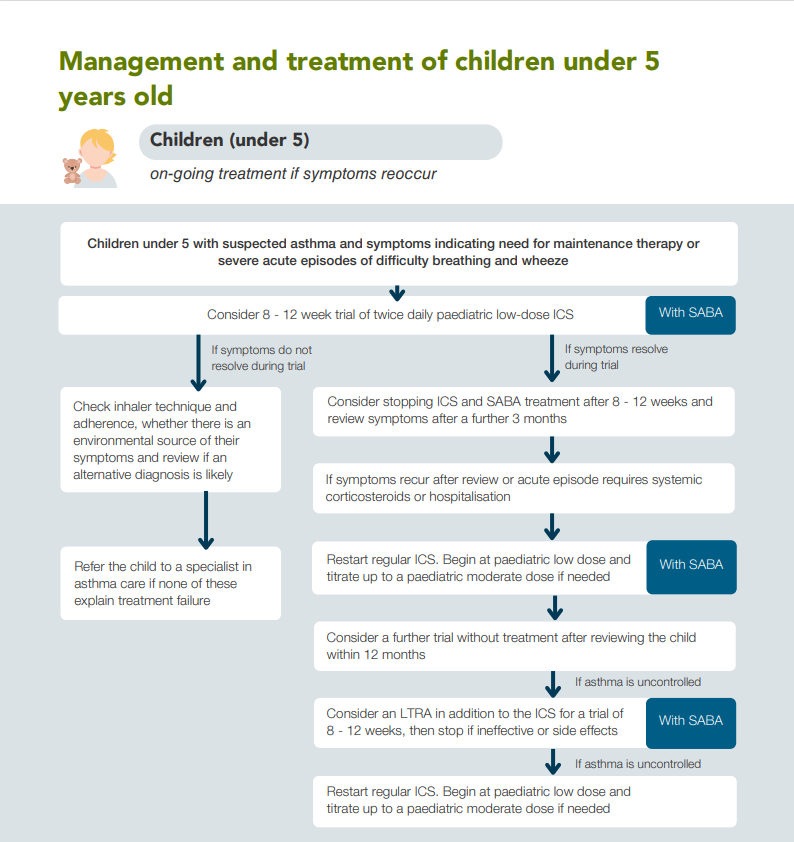

Starting a trial of treatment

Criteria for a trial of treatment - NICE guideline

If the child has symptoms at presentation that indicate the need for maintenance therapy (for example, interval symptoms with another atopic disorder)

or

severe acute episodes of difficulty breathing and wheeze (for example, requiring hospital admission, or needing 2 or more courses of oral corticosteroids)

If the child meets this criteria, start an 8–12 week trial of twice-daily paediatric low dose ICS, with short-acting beta2 agonist (SABA) for symptom relief. Explain that the child has 'suspected asthma' and will need to do tests once they are old enough to do the tests to confirm the diagnosis.

Children aged under 5 should be given pMDI inhalers with a spacer. Children should move from a spacer with a facemask to a spacer with a mouthpiece as soon as they can drink through a straw.

Demonstrate how to use the inhaler and remember to give an additional SABA and spacer for the child to take to any childcare settings they attend. If the child lives between two homes, you may want to prescribe an additional ICS, SABA and spacer.

Give the child an asthma action plan and upload a copy to their notes. Make sure that their parent or carer knows to share the action plan with anyone who provides care for the child.

Discuss triggers, and how to minimise contact with them, including exposure to cigarette smoke, vaping and air pollution.

For extra support, signpost the family to the A+LUK Helpline and Parent and Carer Network. Laura King and Bart’s Charity have produced a comprehensive information pack for parents and carers, with animations, all of which are available in a range of languages.

Explaining a trial of treatment to families

Explaining a trial of treatment to families

When young children have ongoing cough, wheeze, or breathing difficulties, it can be hard to know if they have asthma. This is because young children often get colds and viruses that can cause similar symptoms, and they are too young to do breathing tests.

A trial of treatment with a low dose of inhaled steroid (often called a ‘preventer’ inhaler) can help work out whether your child’s symptoms are due to asthma. Steroid inhalers are safe, reduce inflammation in the airways and can help prevent symptoms like wheezing and coughing.

If your child’s symptoms improve during the trial, this might mean that asthma may be the cause. We will discuss with you at this point whether we stop the inhaler and wait and see if the symptoms return, or whether we continue treatment.

If your child’s symptoms don’t improve, or only partially improve, we may stop and look at other reasons for your child’s symptoms.

The trial is usually for about 8-12 weeks, and it’s important to give the inhaler every day as prescribed. You will have a follow-up appointment to review how your child is doing.

Please keep a symptom diary or record your child’s symptoms on your phone to hare at the review appointment.

You can contact the GP practice or the A+LUK Helpline if you need any extra support in the meantime.

Reviewing the trial of treatment

After 8–12 weeks, if symptoms resolve

• Consider stopping the ICS and SABA and review the child after 3 months to see if symptoms recur.

• Make sure the child’s family understand to bring the child back for an earlier review if their symptoms get worse, or they are worried.

If symptoms have not resolved during the trial

• First of all check adherence, inhaler technique and any other factors that might be affecting their asthma control. If you find any issues, correct them and repeat the trial of treatment..

• Review the diagnosis: could it be viral wheeze, GORD, or something else?

• If none of these factors explain why the trial has not worked, refer to a specialist in asthma care.

If symptoms recur after stopping ICS or the child has a severe episode requiring oral corticosteroids or hospitalisation

• Restart the paediatric low-dose ICS twice daily and continue SABA as a reliever.

• Titrate up to a moderate paediatric dose if needed.

Review the child within 12 months and consider trialling without treatment again, in case the cause of the child’s symptoms has resolved as they have grown, and they no longer need treatment.

If suspected asthma is uncontrolled

Defining uncontrolled asthma (NICE, 2024)

Any exacerbation requiring oral corticosteroids or frequent regular symptoms such as:

using reliever inhaler 3 or more days a week

or

nighttime waking 1 or more times a week

If the child’s suspected asthma is not controlled, and you have checked adherence, inhaler technique and any other factors that might be affecting their asthma control

• Keep the child on their ICS and SABA regime and add in a trial of a leukotriene receptor agonist (LTRA, also known as Montelukast) for 8–12 weeks.

Montelukast is taken at night time in tablet form. Ask the child’s parent/carer to keep a symptom diary during their trial of treatment. Make sure they know to return if they have any side effects that are worrying them and ensure that you inform the family of the potential for mental health side effects. Report Montelukast adverse effects using the Yellow Card system.

If it is not helping or there are side effects

- Stop the LTRA after (or during) the trial.

If asthma remains uncontrolled

• Stop the LTRA and refer the child to a specialist in asthma care for further investigation and management.

This process is shown in the diagram below: